Humans at Scale

The first thing about world is that it’s big.

The second thing is that it’s hard to understand.

Fortunately, one of the cool things science can do — every now and then — is to demonstrate how some of the big things are connected. There is sometimes an order, a unifying mechanism, or at least a thread.

It was not obvious, for example, that what makes the apple fall from the tree is the same thing that causes the tides to go in and out. But this did turn out to be true. And once that secret unity is fully understood, and fully activated, people can build rockets and go to the moon.

The book Scale, by Geoffrey West, draws out some threads, in a set of beautiful straight lines.

It turns out that metabolism — the flow of energy through a living thing — has a mathematical nature. There’s a principle that connects together how big a warm-blooded animal is, how much energy flows through it, and how long it lives. And the results don’t depend on climate, diet, ecological niche, or even whether the animal flies or swims (!).

These deep facts about bodies hold true over the span of about 6 orders of magnitude in scale — from a shrew to a blue whale. Note that this graph counts upward by powers of ten on both axes.

Life in the big city

We are also finding patterns in the “metabolism” of cities.

Check your intuition: say we select two cities at random, one of them exactly twice the size of the other. All other things being equal, do you expect the bigger one to have exactly twice the creative and economic output of the smaller one? Or maybe a bit less than that, because of the extra traffic and friction of a bigger city?

As it turns out, the bigger city will tend to have more than twice the output of the smaller one, and by a consistent amount: about 15%. This pattern emerges across measures like GDP, wages, patents, number of patent authors, R&D jobs, R&D employers, number of contacts in people’s phones, or volume of phone calls.

Per capita, the city that’s twice as big will be about 15% more generative. This generative quality also includes some things we don’t like, such as crime and infectious disease. Those run 15% above the line, too.

Meanwhile, a different set of factors will consistently fall about 15% below: the number of miles of roadway, the number of gas stations, the quantity of electrical cables and pipes. These grow more slowly than the population.

This doesn’t yet give us a science of cities, or of civilizations, but starts us down that road. We can’t build a rocket with this knowledge. But it’s a thread we can pull.

The Shire and the Mill

And it’s a relevant thread, because, well . . . look around. Just about everything in our lives depends on something or other having been colossally, and successfully, scaled up. The lumber in the floor was milled en masse; the bricks in the wall were made in bulk; the cotton in the pillowcase was woven by the ton. Everything rides on the back of economies of scale. Living in an industrial society is living inside a scaled-up body.

And our feelings are not well-calibrated to the dynamics of this big game we’re in. We know how to feel bummed about its costs, but we struggle to see the secret extra payoff, and so we freak out. When William Blake thunders against the “dark Satanic Mills” in the English countryside of 1804, we feel it deeply. We know exactly what he means. This is why 150 years later, when JRR Tolkien wants us to sense just how much Sauron’s dark influence has sent its fingers all the way into the heart of the Shire, he expresses it through the figure of Ted Sandyman, the miller’s son. While the hobbits were away on their quest, what has he done? He built a big, noisy, ugly new mill.

But of course, what is going on in those dark, satanic mills? They are probably milling grain — that is, making more food in a more efficient way. In the Sussex, England of 1804, during the time that William Blake was (comfortably) living there and writing his poem, about a quarter of the population did not have enough food, and needed to apply to the parish food bank. Malnourishment was common. Children went to bed hungry, and did not appear in any poems.

A few more mills might have been good to have, in fact.

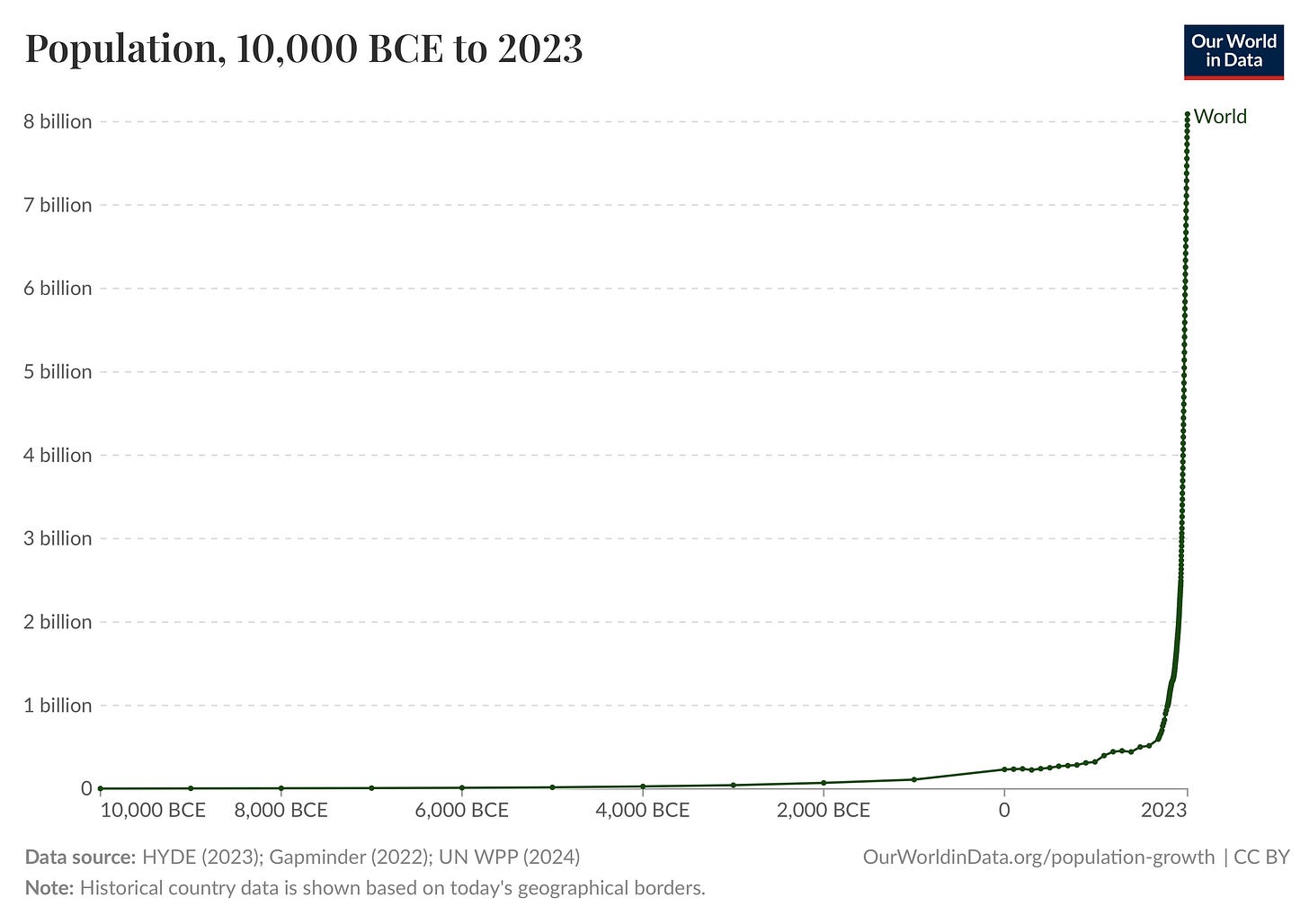

Writers and poets fret about the scale of our civilization, and so do economists and philosophers. Robert Malthus in 1798 famously projected population growth forward, assumed a fixed food supply, and predicted a disaster. In recent memory, Paul Erlich made the same mistake in The Population Bomb. What saved us from these dooms?

It’s the same effect as the extra patents and the extra phone calls. It’s the surplus, the 15% above the line. We humans tend to generate enough good ideas that we keep solving our own problems before they become too bad. This effect keeps on bailing us out, and we can see it continue to do so even today.

Learning Rate

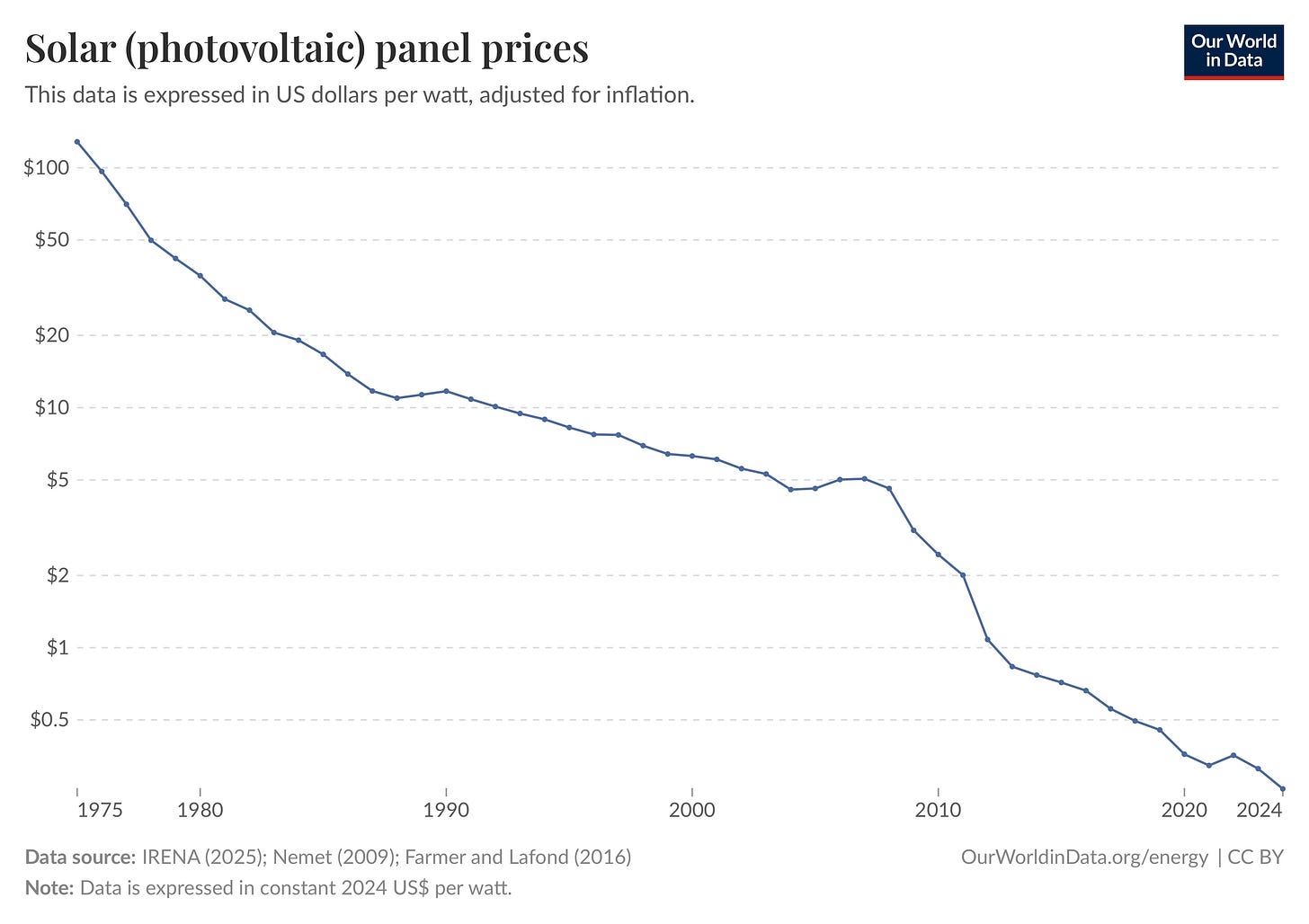

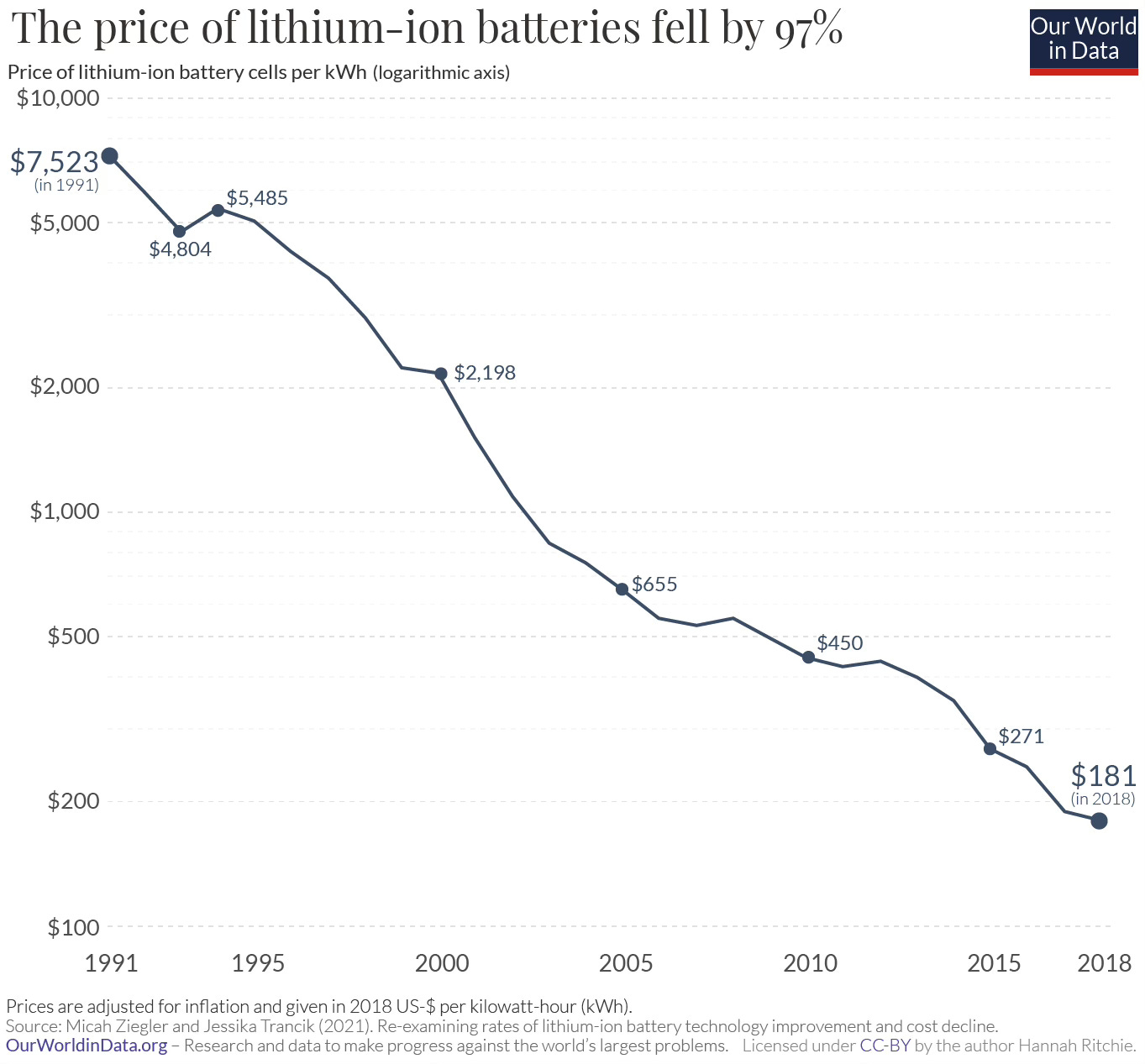

Like this, for example:

And like this:

Note the exponential Y axes — at each step downwards, the price is cut in half.

This isn’t merely a chart of a price decline. It’s a picture of the human species very fundamentally figuring something out.

Now, I’ve been worrying and thinking about global warming since the 1980s, when it was already well understood enough to be featured in elementary school textbooks and in Congressional testimony. (I also had to do a school report on the planet Venus, which is an unpleasant place, so “greenhouse effects” felt vivid to me.)

I live in the city of Los Angeles, where the weather has gotten noticeably, viscerally hotter and drier just in my 15 years here (not to mention the huge swaths of the city that recently got destroyed by unprecedented 70 mph fire hurricanes). I live in one of the global capitals of what is really happening to our climate because of carbon emissions. Venus here we come.

So it’s against that backdrop that I say this: the spectacular fall in the prices of solar panels and batteries appears to me to be one of the most important processes going on in the world right now.

More people should understand this.

This is very likely the thing that bends the curve on global carbon emissions over the next decade.

Not nuclear power, not cap & trade programs, not Kyoto or Paris accords, not carbon taxes, not public transportation, not turning down the thermostat or reusable bags. None of those things are the reason that coal use will actually decline in China over the next 12 months. Or that India has canceled plans for 550 (five hundred fifty) new coal plants in the past few years.

It’s scale that bailed us out. It’s dark, satanic (solar panel) mills. When western countries (especially Germany, Japan, and the U.S.) subsidized the purchase of solar panels, and China increased the scale of production, there was more cost payoff than expected. Processes improved, logistics improved, supply chains matured, more R&D could be underwritten, the technology itself improved, and this added up to a “learning rate” of about 20%. That is, a 20% cost reduction for each doubling in production capacity.

And this flywheel is still going. Which is why today in India, solar power is now 50% cheaper to provision than coal power.

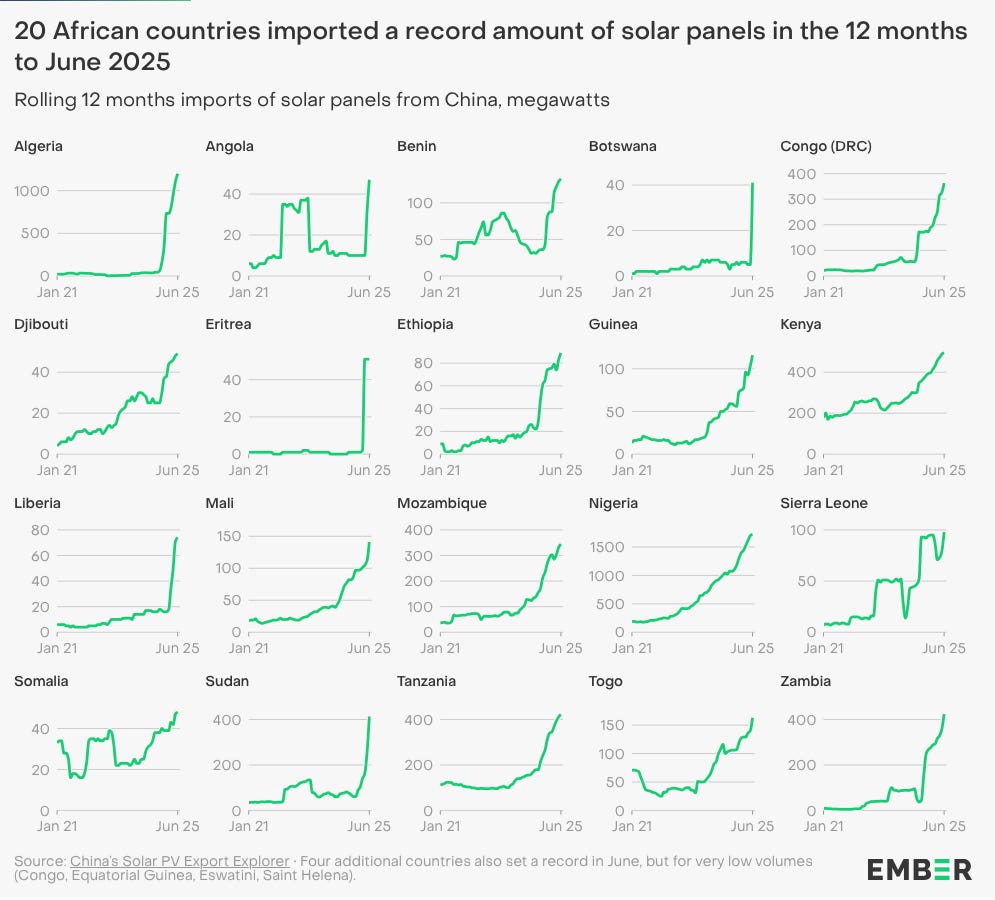

And it’s why this is what's happening with solar power lately in Africa.

Flying Blind

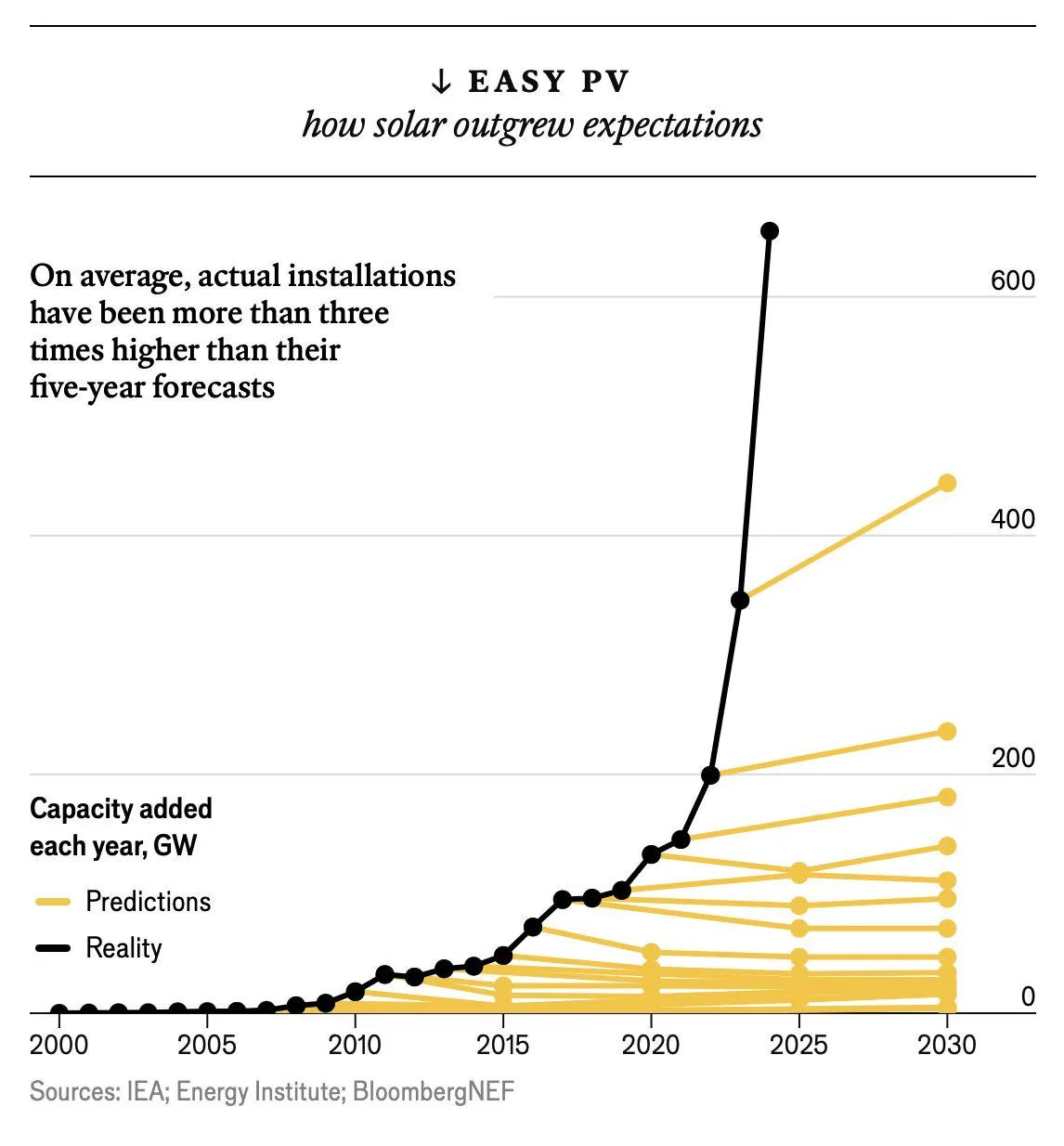

Did smart people not see this coming? They did not.

Take Google — a company that, 25 years ago, basically invented the modern form of computing at scale. Google’s early data centers represented a shocking advance, because they were the first to fully grasp that instead of using fancy, specialized computer servers, they could run the biggest computing jobs on earth using ordinary off-the-shelf computers. The trick was to use a LOT of them.

Now, back in 2007, Google started a green energy initiative called RE<C, based on the (correct) observation that the way to win at decarbonizing is by winning on cost. So the goal was this: find ways to make RE (renewable energy) cheaper than C (coal). Thus the name “RE<C”. How to do that? All their suggestions were technology ideas that didn’t pan out. Nobody at RE<C, before it was shut down, stumbled on the right answer, which was that the way to make renewables cheaper than coal was simply to build a lot more of them. This process was already underway while RE<C was operating, but they didn’t see it.

What about people whose business is energy forecasting? How did they do? How are they doing today? Well, check the expert predictions below, drawn in yellow. Reality is the black line. Yes, so far in 2025 we are 40-50% above the IEA’s predictions from . . . last year.

No, we do not understand scale — how to harness it for good, how to blunt its harms. Sometimes we do a pretty good job, like we did with with microchips (Moore’s Law is of course not a law but an observation about scaling and learning rate). Often we do a pretty bad job: the air quality of New Delhi, the collapsed fisheries in Newfoundland, the “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico caused by fertilizer runoff in the Mississippi River.

What we need to do is to look deeply at scale and learn its hidden ways. We need a science of scale — something that will unify many disparate observations into some principles we can use to finally build a rocket ship. On purpose this time, not by lucky accident.

Leaving the Shire

People want to go back to handmade, to small-scale, to the Shire. But the Shire is a fantasy. We live in this graph, and we live large. This is our home.

In this home, we have unprecedented safety and abundance. You, personally, are almost definitely the healthiest and best nourished and least brutalized person in your entire ancestral line. You very likely didn’t even bury half your siblings, unlike most of the people who ever lived up until around the 1800s. (That link is worth the click.)

But you do live at the tippy top of an exponential graph, riding on the back of a lot of dark, satanic mills, and it’s a precarious feeling. The whole thing is working, but it’s working according to secret rules that we don’t fully understand.

Our lack of understanding is crystallized in that clean straight line of city size versus crime rate in Japan: so many cities, each with a different mayor and a different police chief, different local laws, customs, approaches to law enforcement, different proximity to shipping, smuggling, drug trades, different levels of tourism, immigration, different weather patterns. And yet they all seem to toe a straight line on a graph that they’re not even aware of. It’s almost as though it doesn’t matter which mayor or police chief is in power.

Scale is in power.

And what other lines are we toeing without realizing it? Socially — morally — politically? What hidden principles do we act upon? What connects the apple and the tide, in human affairs?

Outside and alongside every culture, religion, legal system, and intellectual tradition, I think the scale of human society in and of itself is an actor. What is it doing?

And I’ll pull that thread in some future post.